Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

The first listening example that I think is important would have to be Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Op. 125, first movement. This is one of Beethoven’s most popular pieces and is a great example of the use of creating melodic ideas out of nothing and expanding it throughout the piece to showcase an overall thematic melody. This piece is almost a precursor for what is to come in the Romantic era following Beethoven’s death. While composers may find their own individuality in their pieces, the influences from Beethoven is hard to ignore.

The second piece would be Haydn Piano Sonata in E-flat Major, Hob. XVI: 52, first movement. This piece is a good example of Mature late Haydn and includes more of his use of a complicated sonata allegro form. Another interesting aspect is the hint of influence from CPE Bach with the sudden mood shifts and the trio sonata texture.

The last Example i’ll mention will be of the Mozart String Quintet in E-flat Major, K. 614, second movement. This String quartet is a part of a series of pieces that were dedicated to Joseph Haydn, a teacher and life-long friend of Mozart. The music itself is Harmonically innovative and with its unusual instrumentation the lines are expanded in to the lower range

This week we are going to be discussing some questions from Mozart’s Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception. These questions will breakdown performance practices, period instruments, and the ins and outs of symphonies of the late 1700′

I do not personally believe that period instruments are “worth it”. In the article it gives a pretty solid point, “Even if we could fully re-create 18th century sounds, their affect on us would not be the same as listeners from 200 years ago”. I believe this is due to the peoples “modern ear” being that we have been exposed to a higher quality of instruments that were used back then, and that we have been exposed to a vast genre of different kind of music from all over. A pro to attempting to recreate period instruments is that by attempting to recreate these performance conditions of the time, historians and theorist are better able to understand and diagnose what the common performance practices were of that time.

The problem with the laboratory approach to period performances is that these specialist performances are isolated from the critique and influence of public response. These performances are not able to arrive at a high level that is applicable enough to reveal the musical context needed. The Neo-classical procedure also lacks in base. We have no idea of what is really “right” since we do not have a time machine. Everything is based on very close approximations, which still isn’t 100% “right”.

Regarding the quote “for performances to come alive, they must be of our time, not of other times, and that it is the job of the performer not merely to interpret but to reinterpret the music of previous eras.”? I believe that it holds some truth, but also is wrong. While yes, it is best to take old musical ideas that may seem old fashioned/used in excess and make them more modern, it is equally important to note that the era and style of music history is ever changing and adapting. Taking for example how the Romantic era takes us from Beethoven’s 9th and Mahler “Symphony of a thousand” to John Cage’s 4’33, even our current time is just another era being created. One in which none of us might come to know what it will be labeled as.

Orchestras were not standardized in the 18th century. There were not orchestral standards, but more so regional traditions and preferences. It was similar to our time in the quantity of variety and vast musical ideas. Mozart had a habit of adjusting his arias to specific performers strengths’s and weaknesses. This translated into his symphony writing in which he would adjust its form and content based on the ensemble provided and the patrons in which he was writing for.

There were some circumstances that influenced the size of an orchestra in the 18th century. The size of the orchestra usually was a result of economic forces. Downsizing of an orchestra can occur because of a war/depression, or it could be due to the size of the venue its performing in. Patrons, local customs an political changes were also a factor. Koch suggests that an orchestra have at least 6 first violins and 6 seconds. His ratio for churth/theatre orchestras ar 4-4-2-2-2 or 5-5-3-3-2 (Violin 1, Violin 2, Viola, Cello, Double Bass)

The low pitch of a’ = 409 was adapted due to the prized French Instruments being pitched at that level and their standardized pitch travelling with them. “Mozart’s pitch” is based on the pitch he apparently would have encountered in Vienna and some other places at the end of his career.

If one is aiming to do a period performance of Mozart’s symphonies, it would do well to consider the venue. Concert rooms and theaters have changed since the 18th century. An ideal hall would have the the proportions, acoustics, and ambiance of an eighteenth-century concert hall that is small and resonant.

In this blog I am going to be going into detail about the listening examples that we took on our second examination. I’ll be talking about the three that I think would would be best suited to be included on the exam. The basis that I use to qualify and “exam listening example” is based on the composer, the ensemble, and the date of composition.

The first piece that would do well on the exam is the “Haydn Symphony No. 45 in F sharp Minor (“Farewell”), Hob. I:45 (1772)”This piece is the culmination of an interesting bit of history. Haydn’s patron at the time, Prince Nikolaus I Esterhazy, had been keeping his musicians at his summer palace in Hungary. The stay for the musicians had been longer than intended, and the they appealed to Haydn(the Kappelmeister) for help as they wanted to return home. The end of this piece has the musicians leaving the stage as their part ends signifying the “farewell”. The message was received by the prince and the musicians were released to go home. Beyond this the symphony is one of the sole pieces from that time period is in the key of F# minor. Musically, this piece is a good example of Sturm and Drang. The cadences in the minuet is made very weak, creating a sense of incompleteness.

The second example I would include is “Mozart Idomeneo, K. 366 (1781), Overture and Act I, Scene 1″ This opera is an Italian opera seria and it draws from a french influence. This is also Mozarts’ first mature opera and with it; He demonstrated a mastery of orchestral color, accompanied recitatives, and a melodic line.

The third example for the exam I would utilize is “Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824) Violin Concerto No. 22 in A Minor” exam-wise I think it fits well because it gives the most amount of variety. In this movement the performer has a lot of musical lines that are cadenzas. The virtuosic piece shows a good example of standard solo violin rep of that time period.

It’s near the end of the semester when I’m doing this blog, so my final project is pretty much already done/turned in. For those of you reading, the research project included us finding a classical era piece and doing an arrangement for it into another instrumentation. I decided to take 4th movement of Joseph Haydn’s Op. 33 No. 2 titled “The Joke” from the traditional String quartet into a rocking socking Trumpet Quartet. I’m sure Haydn would’ve wanted it so had possessed the modern day trumpet. My project began with finding the perfect resources. Since the project has been done, instead of talking about what will be useful, I’m gonna talk about what resources WERE useful. Enjoy!

Coming in hot with my number one resource is Fanfares and Finesse: A Performer’s Guide to Trumpet History and Literature. I found this resource through Jstor. This resource talks in detail about the history of brass ensembles in general. When I first began the project I had to decide what kind of ensemble I was going to put the arrangement into. With the original piece being a string quartet, I found it the most practical to use a brass quartet(Eventually I would use purely a trumpet quartet). This source was pretty well-written when it came to describing the types of brass ensembles that were available. A typical arrangement would be a Trumpet, French Horn, Trombone, And a Tuba. I didn’t have much experience with any type of brass quartet group, so this source gave me some helpful insight.

The second source that was useful to me was actually a live recording. I watched a live recording of the Attaca Quartet performing the piece. Since this piece is idiomatic to a string quartet, I had to make sure that some of the typical performance practices would still be upheld. This included the appropriate tempos, atmosphere, weight of phrasing, and other performance factors. I found this source by just searching the piece on youtube. Even though it may not be the the best audio recording, it gave me the best idea about how to write for and perform the piece.

The last source that I utilized was “Engaging Strategies in Haydn’s Opus 33 String Quartets. Eighteenth-Century Studies” Due to the nature of this project, the source did not provide that much information in regards to the actual arrangement of the piece. The source did, however, provide very clear and detailed information about the various themes and forms of the piece. I feel as though deep down having a better idea of the piece and its construction assisted in me keeping the piece as authentic as possible.

This week we are taking a gander at the life of Joseph Haydn. Some points to hit will be events that were significant to the development of Haydn as a musician and a person. Kind of a short introduction, but lets hop right on in!

In 1740 at the age of 8, Haydn enrolled in choir school at the St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He began his musical training there, and could soon play both harpsichord and violin. This was vital and attributes to his early knowledge and training as a musician and composer.

Unfortunately, in 1749, Haydn was dismissed from the cathedral choir-school in Vienna at the tender age of seventeen. The best speculation reasoning could be due to Haydn’s voice changing and a combination of being on edge with the music director. With this sudden thrust into the music world, Haydn began freelancing, composing, and doing whatever possible to make ends meet. With Serenades and Divertimenti being the most popular at the time, one of his earliest experiments was a serenade, and, according to one account,it was an improvised performance of this piece that brought him

his first commission and led to the composition of his first “opera,”

Der krumme Teufel.

In 1761, Haydn was appointed as second Kapellmeister to Prince Paul Anton Esterhazy at Eisenstadt. This would go on to be Haydns residence for the next thirty years with the Esterhazys being his patron. in 1766 Haydn was made first Kapellmeister, and a few months later the opening of the magnificent residence Prince Nicholas had built at Esterhaz-with its opera house seating four hundred and its marionette theater again increased his responsibilities, obliging him to devote serious attention to operatic composition, a branch of music in which he had thus far had little experience. This period of him working for the esterhazys also begins the foundation of his reputation among the music world.

1779 was a very significant time for Haydn as his contract with the Esterhazy family was renegotiated. This new contract would offer Haydn a greater amount of freedom to travel to the outside world, and no longer stripped him of the rights to his compositions. This was nearing the end of his period of service to the Esterhazys and would bring about a time when he would visit London, Paris, and Vienna.

Hello my thousands of readers, I come again ready to tickle that classical music bone that you all love and adore me for. This week I will be taking a different type of approach to the blog as I talk about three different listening examples that make good material for my upcoming exam.

The first example is a Trio Sonata in B-flat major by Bach. I bet you were thinking of ole’ Toccata and Fugue in D Minor Bach, but I’m talking about his 5th child C.P.E Bach. This piece is a sort of hybrid binary form, but it has many elements that hint at the beginnings of sonata allegro form. The 2 part solo instruments are a flute and a violin with a cello basso line. The piece does not have very many cadences and the phrasing seems to be asymmetrical. The first 10 bars of the movement sets the “theme” and it’s built upon in some way throughout the piece. I think this piece is an important reference material because of all of the foreshadowing of content that is to come in the Classical Era.

The next example I am choosing is the Symphony in D major op.3, No.2, first movement by Johann Stamitz. This piece is a very great example of what was the typical quality of classical symphony music. yes, this isn’t Mozart, Haydn, or Beethoven, but it still holds true to their top quality of music. The ensemble this music was written for was the Mannheim Orchestra. They were, at the time, one of the best and premiere orchestras. This music reflects that with it’s use of the coup d’ archet and the mannheim rocket. The piece includes a second theme which further hints at the movement towards this sonata allegro form. content-wise, I believe this is a perfect example to have on an exam as its memorable, has a lot to talk about/digest, and just sounds great if I’m being honest.

The last example that I think is important is Domenico Scarlatti’s Song for Harpsichord in D major. This piece is a great example of the shift of baroque era compositions to the more classical era. It combines the counterpoint and seemingly “busy” lines, but still is able to be digested by an audience with its slow harmonic rhythm. This piece also serves as a good basis for the type of virtuoso’s that were performing at this time. With its fast sixteenth note scalular runs and running arpeggio’s, the bar for the average player was set very high.

So this week will focus on some aspects of form within the 18th/19th centuries. I’ll mainly be talking about aspects of sonata form, some theories of tonal music, and the topic of is it necessary to be a form “pro” to appreciate/love classical music. I might try to post some things on the side. I’ve been thinking of this idea of posting things that music majors seem to deal with. whenever this blog is over for class I’ll for sure make something of it

Sonata form for a long time was difficult to pinpoint. It was not an exact form as in the sense of something like a minuet and trio, but more so an expression of style that composers were using. This way of writing seemed to focus more on the melodic structures of various themes within the piece. Now, the main trouble with the 19th century description of sonata form is that brings an importance to the melodic interest of the piece that was not exactly held in the 18th century. Another trouble is that the sonata form is put into this orthodox box that pieces needed to be molded into. Again, sonata at the time wasn’t exactly a form, but a way of writing (like saying “write a piece in Jazz form”) that was eventually given rules and regulations by 19th century theorist.

Now comes a question of did 18th century musicians “heard” sonata form and was it similar to how we hear it today? I believe that they heard the form, but not in the same way that we analyze and hear it in this day and age. Similar to people listening to popular radio songs in the 21st century, musicians of the 18th century probably recognized similarities between the pieces that were composed. I would say the way the way they listen to sonata form was more casual/natural then we would. In our time, we listen to pieces that follow sonata form in a way that analyzes everything that occurs.

In Heinrich Schenker’s theory about tonal music, “the structure of every tonal work is a linear decent towards the tonic. This is interesting because it begins the talk about a type of cadential formula to composers pieces. With this thought, every note within a composition has a meaning and end goal outside of the beat that it happens to occur on. While this is not seen well when looking at single notes/measures of a piece, taking in the composition as a whole points to this pattern.

I feel as though there is this kind of “elitist” type attitude that one must be fully understanding of all the intricacies of classical music to appreciate it. I agree with this in some ways. It’s easy to write off certain genres of music without having at least a ground base of knowledge about it. Hip-hop, Heavy Metal Rock, Jazz. Without having an idea of what is exactly going on, then it is hard to determine what exactly is quantifying a particular song/piece as good or not.

The importance of motivic relationships in the classical era is that it is one of principle means of integration into Western music since the 15th century. This is further seen by the Classical era’s style of nature and simple music juxtaposed with the Baroque era’s style which is best described as fortspinnung ( German term conceived in 1915 to refer to a specific process of development of a musical motif. In this process, the motif is developed into an entire musical structure by using sequences, intervallic changes or simple repetitions. this gives the music a “spinning out” feeling until everything comes full circle) These short motifs not only generate melodies, they determine the entire color and feel of the piece.

So this is my first blog post of (hopefully) many! Since this blog was initially created for my Classical Era music history class, the first series of blog posts will center around topics chosen by my professor. I’ll try to format everything in a way so it’s fluid when read vs. just question/answer. The book I will be referencing all my sources from will be “The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven” by Charles Rosen. if I use any other sources I’ll of course mention them as needed. Enjoy!

Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven are seen as very influential figures of the classical era (Beethoven would bleed into the romantic era). E.T.A Hoffman was a music critic of this era who held a high respect for these three figures of music. He would go on to consider them the first “romantic” composers due to their personal developments of musical art at that time. Hoffman also goes to mention that many at the time many composers tried to give the impression of the real thing (this “real thing” being the quality of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven’s quality of music).

According to Rosen, the classical style developed due to the musical consumer’s desire for a mode of understanding. The Baroque era ended in the 1750’s, but at the time it wasn’t seen as a concrete “this is the end of Baroque”. Mozart would have still been able to have composed a quality Baroque piece, but he instead took the coherent/musical language of Baroque and brought it to his own form of expression. This was the desire of the audience of that time from the likes of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven.

The topic of art/music history can be described as problematic. This is due to the fact that only what is seen as great works, not just the the typical works, lays a claim to our attention/study. for a example of this think of a popular musical artists. While they may have a high volume of music released, only their “big radio hits” are remembered by the casual listener. A misinterpretation this brings is that whatever an artists’ greatest work is is the norm of their personal style, not simply the exception. This disregard for the average works of any specific era contradicts the possibility of a precise agreement of what is art/music history.

Now days classical era music is often seen as background music for some funny videos or for your average college student to study to. With the comings of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven also came a slew of minor composers who are still only known as anonymous to this day. many of these minor composers held habits that simply were being phased out and no longer made sense in the new concept of music. It is only Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven’s works that all the elements of music-melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic- work coherently together to stand the test of time. They all had their own way of standing out among the vast amount of composers.

During this time of history, the definition of tonality was not quite specified yet. Rosen goes to describe it as unbalanced. He seemed to be conflicted as to whether it is based upon the circle of fifths with triads and whatnot, or based upon the major and minor scales with modal centers. Another system he mentions is Equal Temperment. This forces an equal distance between the 12 notes in a chormatic scale and distorts the relation to their natural overtones

The tonic-dominant relationship was seen as very important in the 18th century. Moving from a note to the dominant (or by 5ths e.g C-G-D, etc). This works well because it builds upon the overtones of the previous note. The dominant movement outweighsmoving in subdominant direction (by 4ths e.g. C-F-Bb, etc) which uses the previous not not into a central note of the triad, but an overtone. This imbalanced leads to the basics of tension and release within music for centuries

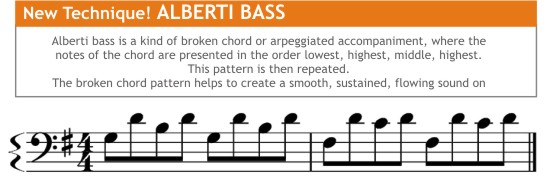

The Alberti Bass was significant in the 18th century due to its destruction of the linear aspect of music from being purely horizontal. This change includes a more vertical aspect of music that was typical in Baroque accompaniment figures. Alberti bass breaks down the voices by integrating them into a line with the chords being within constant movement.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.